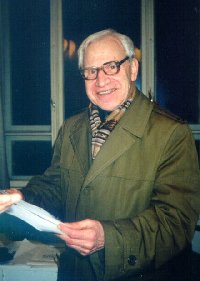

One-time University of Tartu Student Tõnu

Karma reached the Livonian coast for the first time in 1948. Now,

50 years later Karma lives in Riga, the city where most remaining

Livonians reside today.

One-time University of Tartu Student Tõnu

Karma reached the Livonian coast for the first time in 1948. Now,

50 years later Karma lives in Riga, the city where most remaining

Livonians reside today. Toomas Tombu

One-time University of Tartu Student Tõnu

Karma reached the Livonian coast for the first time in 1948. Now,

50 years later Karma lives in Riga, the city where most remaining

Livonians reside today.

One-time University of Tartu Student Tõnu

Karma reached the Livonian coast for the first time in 1948. Now,

50 years later Karma lives in Riga, the city where most remaining

Livonians reside today.

"The Livonians are to blame for the fact that I became a Latvian citizen", says 74 year-old Tõnu Karma on the subject of Livonians, giving some insight into his own life as well. It is difficult to speak about Livonians without mentioning Tõnu Karma. It is even harder to speak of Karma and not bring up the topic of Livonians.

In 1948 a group of students from the University of Tartu visited the coastal villages of Livonia, led by the legendary grand old man of language Paul Ariste. This was the first such expedition following Worid War II. In the period immediately after the war approximately 800 Livonians lived in 12 villages dotted along the coast of the Gulf of Riga; now only about fifty Livonians remain. On the eve of World War II, with the occupation of the Baltic States, the Livonian coast became the western border of the Soviet Union.The beach was closed, barbed wire blocked access to the sea and the beach's sand was harrowed. The Livonians, who had earned a living fishing, were now forced to search for work elsewhere. And so it is that the majority of Livonians now live inVentspils and Riga.

The students participating in the research expedition went from village to village and recorded the language."After a few weeks you got a grasp of the language and could start struggling to communicate in Livonian," recalls Karma. "Learning the language was made easier by the fact that the Livonians had close ties with the Island of Saaremaa and therefore a large number of them spoke Estonian." According toTõnu Karma, the influence of Latvian on the Livonian language caused it to seem foreign. In order to better understand Livonian, he decided to learn Latvian. He thereby began studies in Latvian at the University of Tartu, which lasted two years. Expeditions continued to be held each summier and Karma participated in the following two research trips as well.

In continuing the description of his life, Karma is forced to make a slight deviation into Stalinist language theory. He speaks of how the Soviet regime eliminated the educated who were disloyal to those in power, labelling them as bourgeois nationalists. Those who were given this title of "enemy of Communism" had to repent. Those who expressed regret were spared a trip to Siberia, yet lost their jobs.

This is what happened to the most renowned specialist and researcher of Baltic studies of all times, Janis Endzelins, who worked at the University of Riga. Endzelins refused to accept the theory coined by Soviet linguist Nikolai Marr, according to which numerous different languages fused together as time passed, thereby decreasing the total number of languages in existence.This type of theory suited the ideology of the time to a tee. Every instructor of philology was forced to lecture on Marr's theories. Endzelins was the only one against this and announced that he did not accept Marr nor his ideas. Endzelins was removed from the university, since he had become a bourgeois nationalist. Estonian Paul Ariste was called upon to continue Endzelins' uncompleted work. "Then a young Latvian student came to Ariste for a consultation," explains Tõnu Karma. "By this time I had studied Latvian for a few years and Ariste told me to take the girl out on the town until he freed up, this is how we got acquainted.We wrote to each other for five years and it got to the stage that one of us had to leave our homeland. We decided that it would be easier for me to find work in Latvia than for her to do the same in Estonia." Karma immediately began working at the library of the University of Riga. Research into the culture and language of the Livonians could now continue. Karma became a renowned linguist/philologist.

When courses in Livonian language and cultural history were introduced at the University of Latvia in 1995, Tõnu Karma took up a post as instructor. This Estonian residing in Riga is now an honorable member of the Latvian Academy of Sciences. Estonian president Lennart Meri has presented Karma with the Order of the White Cross and Latvian president Guntis Ulmanis has granted him the Three Star Medal. "I'm not sure what Order I'm supposed to wear them in", ponders Karma.

Karma is one of 1300 Estonians with Latvian citizenship.When the Baltic States regained their independence, people had to decide whether to apply for Estonian or Latvian citizenship. Latvia offered its politically repressed citizens certain benefits and this is what swayed Karmas decision.

"I have experienced prison camp life in Russia; one and a half years in seven different spots.The first was truly a death camp. In August of 1944 I was recruited into the German army, into a reserve regiment of the border guard consisting of Estonians. We didn't get a chance to fire a single shot when the Russians advanced. Who wanted to, stayed here, who didn't, left for the West. I thought to myself, "I haven't managed to do anyone any harm..., I was even wearing civilian clothes," recalls Karma.

There are 186 Livonians holding Latvian citizenship. Livonians, who have been declared Latvias second indigenous people alongside Latvians, lived on the territory of the current Republic of Latvia before the Latvians. It has been reported that Livonians inhabited these regions 5000 years ago. However they were not Livonians, but their ancestors.

The Livonians' cultural life, which had gained momentum during the first period of independence and was stopped short by the Soviet occupation, was re-born along with the newly independent Republic of Latvia. Livonian Days are now held on the Livonian coast each year during the first weekend of August. The central site of celebrations is the village of Mazirbe (Ire in Livonian), where there is a cultural center, school and church, whose construction was supported by kindred Hungarians, Finns and Estonians. There is also a fishing boat cemetery in Mazirbe - fishing boats sawed in half lie rotting on the forest floor Karma reveals the traditions: "Boats were sawed in half before as well.The old ones were used to hold fishing gear and smoke fish. Boats that were no longer seaworthy were used for Midsummer bonfires.That boat cemetery in the Mazirbe forest - before the occupation, boats were never left to rot like that."

Livonians make up a small group: they have one cultural center, five vocal ensembles and their own representative in the Latvian parliament. The first book to be written in Livonian was published in 1863 and from then on approximately fifty Livonian language books have gone to print. In 1935 the first Livonian language textbook was published. Throughout history approximately 30 people are known to have written poetry in Livonian, among them one Estonian, one Latvian and one Finn.

"Never has there been a Livonian language school or church", says Tõnu Karma, revealing the fragility of Livonian culture. However church services have been held in Livonian, presided by young Finnish pastor E. K. Erviö with a degree in theology from the University of Helsinki. "He travelled to the Livonian coast a few times a month. Initially he went from village to village christening children, then he learned Livonian and held sermons in the regions native tongue. This was interrupted in 1937", explains Karma.

The last time the Lord's Prayer resounded in Mazirbe church was a few summers ago when a Service was led by Edgar Valgama, a Livonian living in Finland. Even though Livonian villages lie along a 60 km strip of coastline, the language has three dialects: eastern, central and western. Books have been written in all three dialects. Livonians living in the south-west corner of Estonia never got as far as the printing of their own book. The first Livonian book (the Gospel of St. Matthew) was not published by church clergymen, but rather on the initiative of those studying the language. An attempt was made to preserve Livonian language and culture through the written word.

"Petõr Damberg spoke of how they got out of the path of advancing World War I by crossing the sea to Saaremaa on foot and that they had that book with them. All of their other books were in different languages but one book was in Livonian," is how Karma describes the experiences of the author of Livonians' first reader. Written material in ones native tongue holds immense value for members of a small national group.

Today only eight people speak Livonian as their mother tongue.The youngest among them was born in 1926. In response to the question, could children still be born into families with Livonian as their first language, Karma's explanations take us to Finland. He speaks of a minister living in western-Finland in whose home Livonian is spoken.

Tõnu Karma: "He has bibles in various languages as well as the New Testament in Livonian. He acquired the language based on that book, without ever having had any direct contact with Livonians. It so happened that one night the phone rang. I can't remember whether he asked in Estonian or Finnish, if we could chat a bit in Livonian. I said why not. We spoke for about half an hour.

Juha-Lassi Tast has a large family. He makes a point of speaking to his sons only in Livonian. Tõnu Karma feels that the survival of Livonians lies in their owr hands.

Valt Ernstreit has become a pillar of Livonian cultural life.The Student of Balto-Finnic languages at the University of Tartu was behind the publication of an anthology of Livonian poetry, among other projects. A vocal ensemble has now been formed whose members are all young Livonians. Tõnu Karma believes, ''Our own literature and songs - this also helps keep the Livonian language alive".

""Blow, Wind" is

undoubtedly the most popular Latvian folksong. Now its origin is

thought to be Livonian. One day whe Livonian is no longer spoken,

at least the song will endure."