From Järva Teataja July 8, 1997, p. 5

Genuine Indians at Roosna-Alliku

By Helena Hoksch

Estonians have acquired a perhaps too exotic notion of

Indians on the basis of adventure novels. In fact, the redskins

of today live much like the white man: they have jobs, watch

television and munch chips.

The Indians of the Canadian Cree tribe who performed on the

Horse Day of Roosna-Alliku spoke to Järva Teataja

of their ordinary life.

The group of mostly young Cree Indians living on Sturgeon Lake

Reserve in Canada was brought to Estonia by the society for

culture exchange named Thunderbird, headed by the

well-known Indian researcher Omar Volmer.

The Indians toured Estonia in a big bus about Estonia from

Midsummer and gave the final – the sixth – concert at

Roosna-Alliku.

According to Volmer, the Cree (in their own language the kenistenoag

‘the first people’) are one of the largest Canadian tribes

who in the good old days were woodland Indians but after the

acquisition of horses took up buffalo hunting. They have not

fought the whites but have waged war on their neighbouring

tribes. By the way, Cree women are considered very beautiful and

diligent.

To dance, that is, not to drink

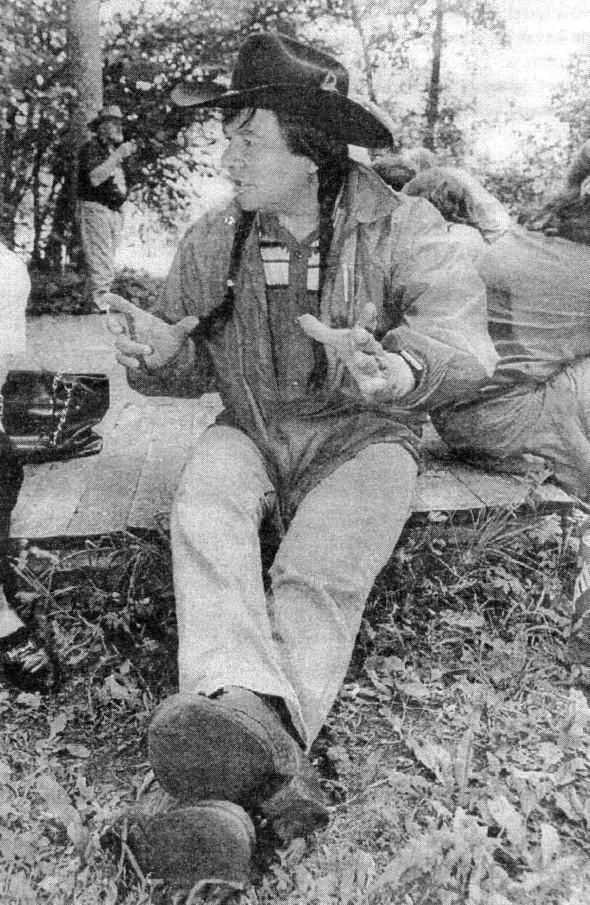

Järva Teataja got the

chance to talk to one of the eldest members of the group, Terry

Daniels. He earns his living at home as the school bus driver and

a social worker. For him, as for the rest of the company of the

redskins, this trip was the first time to visit a foreign

country.

Järva Teataja got the

chance to talk to one of the eldest members of the group, Terry

Daniels. He earns his living at home as the school bus driver and

a social worker. For him, as for the rest of the company of the

redskins, this trip was the first time to visit a foreign

country.

‘We live just like ordinary people,’ said Terry, who has

two coal-black pigtails and wears a cowboy hat. He is wearing a

shirt of Native design and a red jacket that has been printed

just for this year’s tour. In his ordinary life, the Indian can

be distinguished from his light-skinned countrymen only by his

red countenance and his eagle eye.

Terry lives along with a thousand other Indians on the

reserve, another thousand of the tribe live in the nearby towns.

There are nineteen different families and as many last names.

Within the territory of the reserve, every family has a piece of

land and a house at their disposal. The houses belong to the

respective families but the land is the common property of the

tribe. Terry admits that it can be considered a kind of

communism.

Indians have all kinds of jobs, working as mechanics at

wood-working factories, as teachers or social workers at schools

and so on. ‘The only thing that distinguishes us from the white

is our culture,’ nodded Terry. The tribe gathers for a special

event and everyone wears their colourful feathers every weekend.

Thus the dances performed in Estonia are not a part of the

Indians’ everyday life but merely a hobby, just like (Estonian)

folk dances are for Estonians. ‘That is one way not to drink

alcohol or use drugs in the spare time,’ Terry said.

When the journalist tried to explain the Indians that the

ordinary Estonian pictures an Indian as a true savage who makes a

fire in the evening and goes hunting in the forest, Terry did not

at all raise his eyebrows. It is true that there are still some

Indians who live like that even today but they are in the

absolute minority. Terry named a tribe whose name sounds like the

cry of a wild bird and who live in a forest camp all year round.

‘We abandoned that kind of lifestyle since it did not give

us the possibilities equal to those of other people to survive

and manage,’ said Terry. ‘We had to cope with diseases and

famine.’ So that one may love one’s culture but should not

become its slave. Culture is no dogma. Terry claimed that the

Indians still dwelling in the forests do not at all consider

their urbanised kinsmen traitors.

In the ancient times it would not have been possible for an

Indian to get on an airplane and to fly, for example, to Estonia.

The money for the trip of Terry’s group was allocated by the

Prince Albert region First Nations Government Chief – there are

special funds for the Indians’ culture exchange visits to

foreign countries. The Estonian side did not pay the Indians any

fees.

The Indians who have toured Estonia for more than a week were

most amazed at the fact that our language is so viable and strong

that the majority of a people so small speak their own

language only. Many Estonians were unable to communicate

with the Indians in English.

Indians have not been able to keep their language that well

and their homes have become bilingual. Children do not want to

communicate with their parents in their own language since they

have to speak mostly English at school.

‘We might well be the last generation speaking Cree,’

Terry added sadly. ‘We are a changing people whose only serious

problem is our fading national language. That is also our

greatest concern.’

During their visit, the Indians had to admit that Estonians

are very beautiful creatures. Terry found it nice that people

here still believe in nature like the Indians. At least so it

seemed to him. He has heard that Estonians gave offerings to the

forces of nature before Christianity became dominant in Estonia.

‘This is our greatest similarity,’ he deemed, ‘for we still

do so. We do not have a god of our own but we are not Christians.

We believe that there is one God, the God of all.

Above all, we believe in our culture.’ At whiles, an Indian

goes into the forest by oneself and just prays there.

Indians are not rich

The domestic life is much like that of the Americans. Wives

have jobs and husbands help them with housework. Both parents are

responsible for the raising of children but often grandmothers

look after the children too. There are five children in an

average Indian family.

‘We would not like to admit it but even our women have

abortions and are unfaithful to their husbands,’ said Terry.

‘Divorces also occur. But it is not a part of our culture.’

Indians usually marry at about twenty. Nothing much remains of

the old customs of stealing or buying the bride by today but the

custom that the youth has to ask for the permission of the father

of the maiden for further dating after the first meeting can be

considered the last remain of these traditions.

As a rule, Indians are not rich, rather the opposite. Many of

them depend on the social security system and social benefits.

‘I do not know what you mean by rich,’ shrugged

Terry. ‘We are not rich in the classical sense. But we can

manage. Every family has a car and most of what one needs at

home. There are businessmen only among our leaders.’

When asked whether the Indians were happy, Terry considered

the matter for some time and replied: ‘Yes, I am happy. But

many of us are unhappy. Thinking it over, even about half of us

might be unhappy.’

Back

Järva Teataja got the

chance to talk to one of the eldest members of the group, Terry

Daniels. He earns his living at home as the school bus driver and

a social worker. For him, as for the rest of the company of the

redskins, this trip was the first time to visit a foreign

country.

Järva Teataja got the

chance to talk to one of the eldest members of the group, Terry

Daniels. He earns his living at home as the school bus driver and

a social worker. For him, as for the rest of the company of the

redskins, this trip was the first time to visit a foreign

country.